The Ingoldsby Legends, Ingoldsby Country & Tappington Hall

Rev. Richard Harris Barham ~ The "Thomas Ingoldsby" of literature was born at Canterbury, December 6th 1788.

His family had long been residents in the archiepiscopal city, and had estates in Kent. He used to trace his descent from a knight who came over to England with William the Conqueror, and whose son, Reginald Fiturse, was one of the assassins of Thomas a' Becket (see above). Part of the family estate included a manor called Tappington Wood, often alluded to in the Ingoldsby Legends. One of the most famous stories being "The Spectre of Tappington", which mentions Denton and of course Tappington Hall itself (referred to as Tappington Everard).

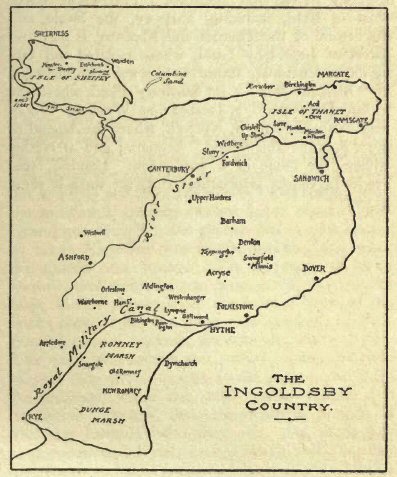

Charles G. Harper, author of "The Brighton Road," "The Bath Road," in his book, "The Ingoldsby Country," points out the literary landmarks of the "Ingoldsby Legends," by "Tom Ingoldsby," the Rev. Richard Harris Barham. The latter was born at Canterbury, the capital of the Ingoldsby country, which he created with his legends.

The following is an extract from Bygone Kent Vol.9 No.9 - September 1988

'THOMAS INGOLDSBY OF TAPPINGTON HALL'

By Alan Major

The 'Ingoldsby Legends' by R.H. Barham, were the first burlesque and horror

tales in verse in the English language. Their creator was a clergyman of

Kentish origin whose lifestyle and character was at times equally unusual.

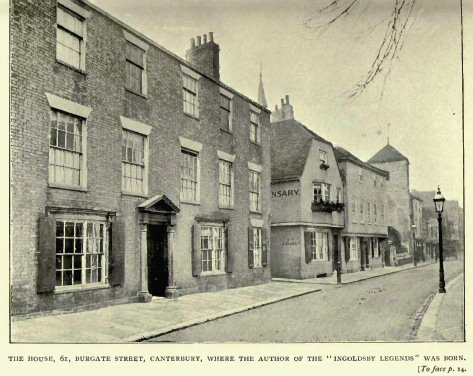

Richard Harris Barham was born at 61 Burgate, Canterbury, on 6th December

1788. His was an old Kent family that claimed descent from the De Bearhams,

anciently the FitzUrses, one being a knight involved in the murder of Becket

who, having fled to Ireland, left his manor of Barham to a brother who

changed the family name to De Bearham which in time dropped the De and was

corrupted to Barham. At some time the manor had passed out of the Barham

family but eventually returned. A Colonel Thomas Marsh sold it to Thomas

Harris, Canterbury hop-factor, the latter dying in 1729. Harris' only child,

a daughter and heiress, married a John Barham. The Rev. Richard Harris

Barham of 'Ingoldsby' fame was fourth in descent from John Barham.

His own father, also a Richard Harris Barham, was a Canterbury alderman and

mayor and inherited the Burgate property from his father Richard Barham in

1784. Alderman Barham was enormously fat, weighing 19 stone, though one

source says 'seven and twenty stone before he was 48', but he formed a

relationship with his housekeeper, Elizabeth Fox, of Minster-inThanet, the

result being the birth of their only child, Richard Harris Barham, four

years after they moved into the Burgate house. The child was baptised nearby

at St Mary Magdalene church, Burgate. Barham's father died in 1795 and was

interred at Upper Hardres. His son, at the early age of seven, thus

inherited the Manor of Tappington Everard, near Denton.

Richard Harris Barham, the younger, began his education at Canterbury, but,

being fatherless, he was sent aged nine to St Paul's School, in the

Precincts of that Cathedral.

At St Paul's School he was a friend of Richard Bentley, later to be his

publisher. While returning there in 1802 he had been involved in a coach

accident that was almost fatal for him, but recovered although his right arm

was permanently crippled. Barham later described himself at this age as 'a

fat little punchy concern', a description that fitted him for life, too, as

he remained a short person, broad and deep-chested.

He went to Oxford in 1807, where he achieved his B.A. degree in law after a

somewhat wild, extravagant undergraduate life including heavy gambling

losses. A guardian, Lord Rokeby of Monk's Horton, refused to pay these

debts, but gave Barham the money as a friend the sum he would not lend. This

so impressed Barham that he changed his way of life and returned to his

Burgate property. There he founded the convivial Wig Club, whose members

held burlesque debates in the summerhouse of the high-walled garden fronting

Canterbury Lane and even paraded in fancy costume along Burgate.

In 1813 Barham's mother died. He also endured a serious illness. During this

his views on his future changed. Instead of the law he decided to enter the

ministry and was ordained that year. In 1814, on being appointed curate of

Westwell, he married Caroline Smart, daughter of a captain in the Royal

Engineers.

The Archbishop of Canterbury presented him with the living of Snargate and

curacy of Warehorne in 1817. Far from being disillusioned at this

appointment to an isolated Romney parish it suited him admirably. Many of

his parishioners were smugglers by night, who, when there was a 'run' of

goods, commandeered his church belfry to stow them. Perhaps some came his

way for 'turning a blind eye' to such occurrences.

While at Snargate he had a gig accident and broke a leg that confined him to

home. To pass the time he wrote his first novel 'Baldwin', published 1820,

but it was not successful. Undaunted he began another, 'My Cousin Nicholas',

but in 1821, elected a Minor Canon of St Paul's Cathedral, he left Romney

Marsh for London with his wife and three children.

In 1824 he was presented with the living of St Mary Madalene and St Gregory By

St Paul's, and made Priest in Ordinary to the Chapels Royal. He now found

time to write topical and religious articles and poetry for various

publications. This brought him into contact with literary people, including

a Mrs Hughes, grandmother of Thomas Hughes, author of 'Tom Brown's

Schooldays', the result of which being that he finished 'My Cousin

Nicholas', published in parts in 1834 by Blackwoods's Magazine. As a book it

was not a great success: Barham found it difficult to sustain novel writing

although he wrote verse with ease.

Probably 'Ingoldsby Legends' would never have been created either but for

his desire to help his old school friend Richard Bentley who was to publish

the first issue of 'Bentley's Miscellany' in January 1837, edited by Charles

Dickens. Bentley persuaded him to contribute to it.

Mrs Hughes was also involved in launching what became the 'Legends'. She was

a mine of ghost stories, folklore, mysteries and topographical traditions of

all kinds which Barham revelled in hearing her relate. She gave some of her

themes to Barham to put into verse, as he freely admitted: 'Give me a story

to tell and I can tell it in my own way but I cannot invent one'. She also

advised him to use some of the suitable examples from his Kentish background

and the county.

The 'Ingoldsby Legends' were published periodically in 'Bentley's

Miscellany'. The first was 'The Spectre of Tappington' in January 1837,

under the pen-name 'Thomas Ingoldsby' in case it was thought unseemly for a

Minor Canon of St Paul's to be the creator of such verses.

Readers became curious about 'Thomas Ingoldsby'. They wanted to know where

he lived; did he visit London, if so, when, so readers and literary men

could meet the 'Legends" creator. Dickens as editor was pestered with

enquiries and replied he knew nothing of 'Mr Ingoldsby' who, he believed,

only Mr Bentley had ever met. Dickens was certain, too, that Mr Ingoldsby

was a shy, retiring man and he had made an arrangement that Mr Ingoldsby's

'copy' of the verses went straight to the printer, so the editor never saw

it. Was this not unusual, he was asked, but Dickens replied that as everyone

knew Mr Bentley had his own way of doing things.

After their success in the magazine it was decided in 1840 by Bentley to

collect some of the verses as a book, 'The Ingoldsby Legends by Thomas

Ingoldsby'. This was a success. Then the truth came out. 'Thomas Ingoldsby'

was none other than the Rev. Richard Harris Barham, but whatever

embarrassment and unease he feared with the Church did not materialise; the

opposite was the case and he was soon enjoying fame. A second edition

appeared in 1843 and a second series had been added to the original edition

in 1842, while a third series being added to the first and second series,

all in one volume, was issued in 1847, introduced by his son, Rev. R.H.

Dalton Barham, who died at Dawlish in 1886.

But what of Barham the man and his ancestral home Tappington? He preferred

to write at night often aided by a glass or two of gin. He was devoted to

cats and his pets sat on his writing table or one even perched on his

shoulder while he worked. He was thus described in an obituary: 'as a man

Barham was exemplary, a pattern Englishman of the most distinctly national

type. The associate of men of wit he passed through life with perfect credit

as a clergyman and a universally respected member of society.'

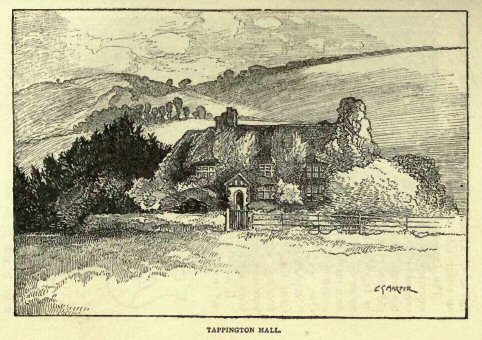

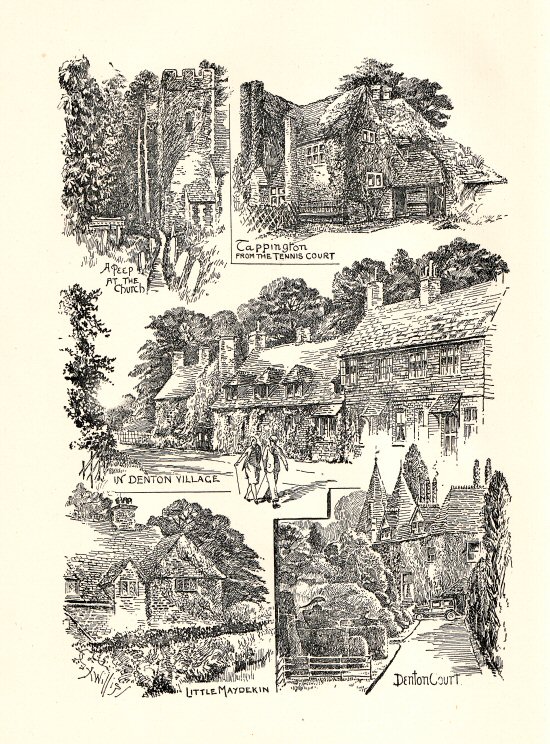

Tappington is mentioned in Domesday Book as Tupton, later known as Tapton

Everard and Tappington Everard. The present red brick and timbered building

is Tudor, altered much since built by Thomas Marsh of Brandred about 1628,

set at the foot of two Downland escarpments and reached by a farm lane from

the Canterbury-Folkestone road.

During a recent visit on a grey, overcast, windy day, within its rooms it

was easy to imagine Barham writing at night by guttering candle or lamplight

while the wind through the valley created cold draughts around the

staircase, and howled in the chimney, while outside the branches of trees

clashed together, all establishing the atmosphere he needed for his verses.

The Tudor staircase, with its carved oak balustrade and mould handrail, has

a newel post on which is carved the reputed merchants' mark of Thomas Marsh

of Marston in Barham's 'The Leech of Folkestone'. One night during the Civil

War a fratricide was supposedly committed on this staircase, from two rival

brothers, descendants of Marsh, one a Royalist, the other Puritan, living in

separate parts of the house, met on the stairs. The Puritan, full of hatred,

on passing his brother attacked him with an axe and killed him. Mrs Jane

Clough, the present owner, pointed out to me the indentation on the rail

said to have been caused by an axe blow that missed its target, while one of

the balusters also has a piece struck from its base.

No bloodstains are now in evidence on the stairs or the landing near what is

known as the bedroom of 'Bad Sir Giles' who murdered a guest, described in

'The Spectre of Tappington'. Writing in his 'Ingoldsby Country' (A. & C.

Black, 1906) Charles G. Harper stated that in 1904 he could still see the

bloodstained topmost stair and flooring, but Charles Igglesden, Vol.26,

'Saunters Through Kent', on a visit in 1932 said the 'ineradicable'

bloodstains could no longer be seen. Around the frieze of the hall there are

small armorial shields of the 'Ingoldsby family', but, as Igglesden said,

they are 'a quaint hoax'.

Visitors for many years came to see the ancestral home of the 'Ingoldsbys'

and went away confused. Barham, in an attempt to convince the incredulous

concerning his 'Legends' and Tappington Everard wrote: 'Let them take the

high road from Canterbury to Dover till they reach the eastern extremity of

Barham Downs. Here a beautiful green lane diverging abruptly to the right

will carry them through the Oxenden plantations and the unpretending village

of Denton, to the foot of a respectable hill ... On reaching its summit let

them look straight before them ... among the hanging woods which crown the

opposite side of the valley ... an antiquated manor-house of Elizabethan

architecture, with its gable ends, stone stanchions and tortuous chimneys

rising above the surrounding trees ... proceeding some five or six furlongs

through the avenue, will ring at the lodge-gate, they cannot mistake the

stone lion with the Ingoldsby escutcheon in his paws � they will be received

with a hearty old English welcome.' But no such building existed; no

lodge-gate, no stone lion, or avenue to Tappington. His description was

writer's licence on Barham's part, a combination of various buildings and

scenes known to him. Nearby Broome Park mansion and its 'eagle gates were

the originals in Barham's text and Gilks' woodcut 'Tappington Taken From the

Folkestone Road'.

Barham widely used the names of ancestral relatives, his friends and other

people in his work, plus the legends and traditions of Kent and many sites

in the county, too, several being set at Tappington itself; examples 'The

Ingoldsby Penance' and 'The Witches' Frolic' which also refers to 'my little

boy Ned'. Canterbury Cathedral features in 'Nell Cook, a Legend of the Dark

Entry'. 'Misadventures at Margate' concerns that resort. 'Smugglers Leap

�Legend of Thanet' refers to villages in the area, a chalkpit near Acol and

an Exciseman, Anthony Gill, who lost his life there in the 18th century.

Another is 'The Old Woman in Grey, a Legend of Dover', also 'Grey Dolphin, a

Legend of Sheppey', referring to Robert de Shurland and his horse. Studying

them again the reader soon realises Barham's verses on these subjects are

what I would call 'semi-fiction'.

But to return to Barham's life. In June 1840, he received a shock from which

he never recovered � the death of his youngest, favourite son, his 'little

boy Ned' at the age of twelve. This was followed by the sudden death of a

lifelong friend, Theodore Hook, another practical joker and novelist.

Barham attended the opening of the Royal Exchange in 1844, caught a cold,

which he neglected, so it developed into his 'fatal illness'. At his home in

Amen Corner, Paternoster Row, London, he jocularly remarked this was

appropriate due to its name and his end being nigh.

As he lay in bed he managed to reflect his feelings in a last poem 'As I

lave a-thynkyne' written a few days before he died on 17th June 1845, aged

56, having already 'made careful disposition of everything � even the cats'.

He was interred in a vault in St Mary Magdalene, Old Fish Street Hill, but

after a fire in 1886 destroyed the church his remains were re-interred in

Kensal Green Cemetery.

His son, Rev. R.H. Dalton Barham, when vicar of Lolworth, Cambridgeshire,

having no children of his own to inherit it, sold Tappington before he

retired to Dawlish in Devon, and divided the sum raised with his two sisters

and so Tappington for the second time passed out of the Barham family.

On 25th September 1930, a memorial service was held at the Guildhall,

Canterbury, at which a memorial bronze to Barham was unveiled by the Rev.

W.R. Inge, Dean of St Paul's.

During the Second World War Barham's birthplace, 61 Burgate, was destroyed

by German bombing and for a time the bronze plaque was lost, but later

re-discovered. A modern shop now stands on the site and on a wall of it his

birthplace is again commemorated by the plaque depicting a bust portrait of

Barham with the wording underneath: 'Rev. Richard Harris Barham, B.A.,

author of Ingoldsby Legends, son of Alderman Barham, Mayor of Canterbury,

born here December 6, 1788. A humorist, a poet, a genealogist, an antiquary,

a clergyman, greatly beloved. This tablet was unveiled by the Very Rev. W.R.

Inge, Dean of St Paul's, 1930.

The following is an extract from A SAUNTER THROUGH KENT Vol. XXVI (1932) by Charles Igglesden

Illustration by - X Willis

Down in one valley you can see a beautiful old homestead �it cannot escape

your eye, for there it stands quite by itself, save the barns, cattle sheds

and the farm buildings that partly surround it. And out of the midst rise

noble trees of great height, with long spreading branches sheltering the

stock in farmyard as well as those which, having grazed in the fields, rest

in the shaded coolness. For out on the slopes are the cattle and the sheep

of the typical yeoman who is now the tenant of Tappington Hall, Mr. F. P.

King..

Tappington Hall? Yes, my dear readers, those who know and love Ingoldsby

Legends will of course remember Barham's verses built up around this

cherished spot. For he lived here. and other members of his family, too, for

it was the seat of the Barhams-two branches of them. The famous Reverend

Richard Harris Barham was the son of the portly Canterbury alderman of that

name, whose girth was so great that he could never sit in an ordinary

armchair, and when he died the doorway of his house was of necessity

enlarged so as to allow the coffin to come forth.

And now the natural question is asked : Is the Tappington Hall of the

present day the exact original of the Tappington Hall mentioned in

Ingoldsby? In many respects it answers to the description, but, on the other

hand, the iron " Eagle Gates," which give entrance to Broome Park, and

mentioned by Barham, give credence to the truth that the author meant the

mansion within that park as Tappington Hall. My view is that he utilised his

knowledge of the two places and wove them into one to suit his purpose. It

must be remembered that he was a man of imagination, and it is difficult for

a writer possessed of such a temperament to stick strictly to details. He

even twisted the epitaphs on tombstones so that he might exercise his wit,

and many a searcher after Ingoldsby quotations has failed to discover from

whence he culled them. But whether or not Tappington Hall, lying snug in the

valley to-day is an exact replica of the Hall depicted by Barham, its

atmosphere, without doubt, breathes of the generations of that East Kent

family.

Tappington was mentioned as far back as the days when Domesday was

compiled--over eight hundred years ago�but it was then known as 'Tupton and

subsequently as Tappington Everard. The present building, built on the site

of an earlier one, was erected in Tudor times, although it is not as large

as its predecessor, and it has been altered since then. This earlier manor

house must have extended a long way, as its foundations can even now be

found underground. A well still stands a few yards to the rear of the house,

and as wells were enclosed in days gone by for fear of contamination by

ruthless enemies it is pretty well certain that the courtyard extended far

enough to embrace the well within the domain. During the advance of

Cromwell's Roundheads through Kent they visited Tappington, and the owner, a

Loyalist, escaped. His wife and servants underwent a severe examination but

declined to divulge anything they might have known, and it is recorded that

the Roundheads departed after soundly thrashing two farm hands and emptying

the larder of every morsel of food. I wonder if the Loyalist was secreted

all the time in a hidden cupboard under the landing, which afterwards became

the scene of a terrible tragedy.

If the old homestead looks conspicuously beautiful as we glimpse it from the

main road, its front opens up to an additional charm as we go down the

roadway�just a grass tract with ruts for the wheels of carriage or car�for

it is so truly rural, with no big drive and not even a roadway in front of

it or behind it. The visitor leaves his car in a corner close by the

farmyard and walks across the meadow to the little wooden gate that gives

entrance to the garden, which is enclosed by an attractive latticed fence.

And what an old-world garden ! And then, behind are the mellowed brick walls

and windows wreathed in a wealth of ivy and creeper roses, sheltered from

above by a long and slightly undulating roof, whose timber frames have

warped. The deep-tinted tiles, almost golden when the sun shines on their

mossy surfaces, try to show themselves through the masses of ivy with

tendrils penetrating under the eaves and up the chimneys. This ivy, brutal

in its power, has conquered all but the roses which cluster and grow in

front of the house. Ivy in masses, and if you removed it I wonder whether

the roof would come, too.

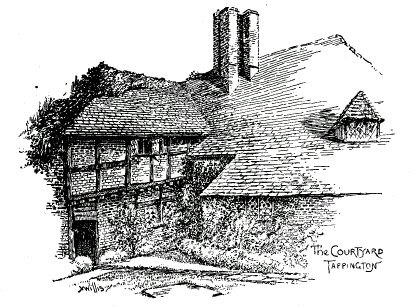

Tappington Hall is to-day composed of many roofs, and yet happily blending'

with each other, and this shows that the interior must have been altered

since it was constructed in the early part of the seventeenth century, and

the filling of the frame was of red brick. From the centre rises a stack

with four separate chimneys, and another original chimney stands at one end.

The three windows in -the front of the house are half dormers with uncommon

sloping roofs, and, like those below them, are latticed. What a difference

does the retention of latticed windows make to the appearance of a Tudor

house !

At the back of the house are several mullioned

windows. But the most artistic spot of all is to be found in a small

courtyard at the back, into which you can peer from tiny windows protected

by a long timbered cave which has become slanting with age. It must not be

forgotten that most of the treasured ancient glass remains in nearly all the

windows of the house, and are, therefore, effective in appearance, if not as

transparent as those endowed with modern glass. The little gabled porch has

mullioned windows, but what astonished me most was to see bees flying out of

a deep hole ire wall by the side of the porch. Mr. King tells me that a

bee-hive has thrived in this spot several summers, and the only thing to

assume is that, far away under the roof, the bees have made excavations and

here they store their honey year after year. The original front door- the

Tudor porch is practically intact, studded with square-headed nails and

deeply-carved panels�a wondrous piece of workmanship.

Within the house you will naturally search for old beams, and you will find

a long one running across the three rooms in the front, but they are neither

massive nor moulded. Most of the doors are very old, many of them still

retaining the bobbin latches. But the most beautiful doors are to be found

in the hall, the panels containing mathematical designs, while the mouldings

are rich and deep, but, strange though it may seem, the inner sides of these

doors, facing the rooms, are plain. The posts of these doorways are of solid

oak, and, taken as a whole, they are probably the most beautiful of any to

be found in a small country house of the early seventeenth century. Round

the frieze of the hall have been erected small armorial shields, painted

with the coats-of-arms of the legendary Ingoldsby family, and some of their

names have been affixed to old pictures on the staircase, the idea being to

carry out the illusion that Tappington was really their ancestral hall. This

quaint hoax which has puzzled so many visitors was skilfully perpetrated

about half a century ago, and was quite in the spirit of the time.

The front of the house was at the present back, and it is the original hall

and the hall of to-day that possesses a treasure to be proud of and,

happily, well preserved. It is a Tudor staircase in carved oak extending to

the upper storey, and in the deeply-moulded newels are the old holes in

which candles could be inserted. The balustrade has moulded handrails. This

spot marks a terrible tragedy dating back to the troubles when families were

divided over the rights of Cromwell and Charles. Two brothers living at

Tappington were divided between the two factions�Loyalists and adherents of

Oliver Cromwell�but continued to live in the same house, each shutting

himself away from the other in separate apartments. By that time the Civil

War was over, but the same feeling prevailed and they never spoke. But one

night, when going to bed, they happened to meet on the stairs. Bursting with

anger and fanaticism, the Puritan could not resist his opportunity. Turning

suddenly, he attacked his brother with an axe and killed him. An indentation

on the balustrade is said to have been caused by the first ineffectual blow

of the axe.

Another owner of the house was known as " Bad Sir Giles," and the ghost of

one of his victims, the young daughter of his gamekeeper, is said to haunt

the coppice not far away. Into this wood he enticed the maiden, and only her

ghost was ever seen again. Barham makes much of another tragic story

connected with Sir Giles, who murdered a guest as he lay in bed one night.

One of the bedrooms is still called " Bad Sir Giles' " room, and at one time

stains on the landing were shown, stains from the blood of the murdered man

as it trickled under the door to the floor outside. I asked Mr. King, the

present tenant, if he had ever seen either of the ghosts�of the Cavalier,

the gamekeeper's daughter or the unknown guest�and he merely smiled. " You

certainly ought to have one ghost, if not all three," I said. Again he

smiled, and said, " We can't have all you want." He could not even show me

the bloodstains on stairs and landing.

Here is a further legendary tragedy, this time connected with a cupboard

under the landing, where, it is said, a boy was confined and died there.

Tradition tells us that he was the unwanted child of a lady standing high in

the world of society and was hidden in Tappington Hall, and there met his

death�murdered, some suggest. Here again is a tale that in itself might be a

fitting background to a ghost story, but, alas ! no one can ever see a ghost

in these old homesteads nowadays. There is a hole in the wall of the

dining-room that is said to have been a priest's hiding-place, but nearly

every residence boasted of a cavity in the walls somewhere, for were not

contraband spirits and silk being continually brought this way from the

coast of Kent?

A further feature of Tappington Hall is a stone Tudor fireplace. The arched

mantel remains, but a modern grate has been installed, set in blue and white

Dutch tiles. The material from which this fireplace was made was chalk, and

we find similar ones at Newnham and other parts of Kent. Carved figures

represent fruit and corn, and a swan. From the kitchen two immense coppers

were taken years ago, when the brewing of beer ceased. But before that time

this apartment was the dining hall, and the seats for farm hands alongside

the wall of the room still can be seen.

In the December 2002 Suzi Perry and the Treasure Hunt Team dropped in to Tappington Hall.

The helicopter heads north, following the A260 Canterbury road (the road to Durovernum) to the village of Denton (a small dent on) and over the temporary studio in Broome Park. Dermot walks to the window and waves to Suzi as she flies overhead. English humourist Rev Richard Harris Barham, who was born in Canterbury, wrote �Ingoldsby Legends� (Barham�s booked it in gold) which featured nearby Tappington Hall. The clue is on the staircase under a notch in the stair rail (Mark to flight).

Suzi flies north again in the direction the village of Patrixbourne (where Patrick�s born). Count Louis Zborowski lived in nearby Higham Park Hall (where Louis lived) and built three three aero-engined cars, all called �Chitty Chitty Bang Bang� (�your fine four-fendered friend� in the film title song). One of the Chittys is waiting outside. After looking under the car�s bonnet, Suzi finds the clue under the hat (bonnet) of the car�s current owner.

The extract and images above are from Martin Underwood's Treasure Hunt website.

Links to local information and websites

Page last updated 19/01/2024.